By Brandon D. Smith, Leslie D. Grush, Kelly M. Reavis, James D. Schultz, Carlos R. Esquivel, and James A. Henry

This article is a part of the July/August 2021, Volume 33, Number 4, Audiology Today issue.

Noise is ubiquitous in the military and has the untoward effect of inducing hearing loss and tinnitus among service members. In 2019, 2.1 million military Veterans had a recognized service-connected disability for tinnitus and 1.3 million had a recognized service-connected disability for hearing loss (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021).

The tinnitus and hearing loss they experience are typically irreversible; affected Veterans may face a lifetime of clinical care to manage the associated symptoms. Auditory function is critical to quality of life and overall functioning—job performance, relationships, communication, and health—among service members and Veterans (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017; Davis and Hoffman, 2019).

Because of increasing concerns about the impact of noise exposure on military service members, Congress directed the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to contract with the Institute of Medicine (IOM, now the National Academy of Medicine) to review the literature since World War II addressing noise in the military and its impact on auditory function.

In 2006, the IOM released a landmark report (Humes et al, 2006) that highlighted large gaps in our foundational knowledge and understanding of relationships between military noise exposure and auditory dysfunction in service members and Veterans. Consequently, the VA could not predict the risk of these auditory disorders in service members who are exposed to noise.

Compounding this problem, many other military and non-military exposures can cause auditory injury or contribute to long-term risk, including exposure to solvents and other chemicals, blasts/explosions and other sources of traumatic brain injury (TBI), and certain other injuries and medical conditions.

It is critical to attain a fundamental understanding of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of tinnitus and hearing loss, as well as their interrelatedness. Such an understanding could help identify individuals at risk for auditory injury and ultimately support the development of rehabilitation methods that target the underlying causes. To better understand the cause-and-effect between military noise and auditory injury, the IOM report recommended that researchers initiate epidemiological research documenting Veterans’ hearing health through the remainder of their lives.

The NOISE Study

In 2013, in direct response to the IOM recommendations for research, an interdisciplinary team of audiologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians was assembled at the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR) located at the VA Medical Center in Portland, Oregon, to design a longitudinal study focused on auditory health in service members and Veterans. This study, named the Noise Outcomes in Service Members Epidemiology (NOISE) study, is a joint effort between the Department of Defense (DoD) and the VA.

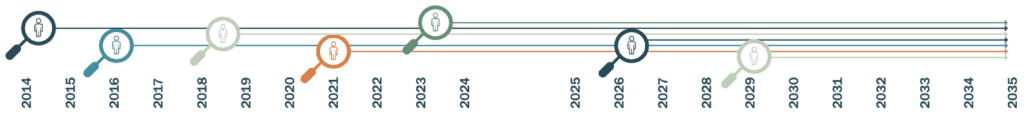

With funding starting in 2013 by the DoD Office of Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, enrollment began in 2014 at the NCRAR. Around that same time, a second study site was established at the Joint Base San Antonio, Texas, in collaboration with the DoD Hearing Center of Excellence (HCE) to enroll active-duty service members. To date, the NOISE study has enrolled more than 1,000 service members and Veterans. A timeline of the study milestones and funding is displayed in FIGURE 1.

The NOISE study enrolls active-duty service members and Veterans within about two and a half years of military discharge, with the intent to collect data from participants over the course of their lives (contingent upon ongoing funding). Participants complete a comprehensive, in-person assessment focusing on tinnitus and hearing function when enrolled and then every five years thereafter. They also complete 14 questionnaires annually (17 if they have tinnitus) to capture demographics, pre-military health, military and non-military exposures (including, but not limited to, noise and ototoxicants), perceived health, functioning, and quality of life related to health conditions.

Currently, 76 percent of the participants who are due for follow up have contributed follow-up data—an important milestone for the success of the project (see FIGURE 2). The NOISE study team maximizes retention in the study through follow-up reminders by phone calls, emails, and postal mail, holiday cards, and study memorabilia tokens provided at the five-year visits.

The use of web-based questionnaires using the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) web application (Harris et al, 2019) contributes to the study’s high follow-up rate. Allowing participants to complete questionnaires at home, where they can access relevant information such as their medications, reduces the amount of time spent on site and is expected to increase the validity of their responses.

Developing Instruments to Capture Critical Data

One of the first tasks of the NOISE study was to standardize its definition of tinnitus, which can improve tinnitus research and patient care by enabling more direct comparison among studies and clinics (Henry et al, 2020b). Because individuals vary widely in how often they experience tinnitus, a four-item algorithmic instrument (Tinnitus Screener) was developed to classify tinnitus as “constant,” “intermittent,” or “temporary” for the purpose of determining whether to administer tinnitus questionnaires and to better define tinnitus for the study’s analyses.

Marines participating in a live-fire training illustrating how service members are often exposed to loud noise and blasts as part of their duties.

Using a sample of the first 100 participants enrolled in the study, an analysis of the Tinnitus Screener data showed a 96 percent predictive validity (Henry et al, 2016). Since then, the Tinnitus Screener has been revised to include two additional items that distinguish “occasional” from “intermittent” tinnitus and determine if tinnitus is acute (less than six months in duration) or chronic (at least six months in duration).

To isolate the effects of military noise on the auditory system, it is necessary to assess noise exposures that occur outside the military context, including recreational noise and non-military occupational noise.To address this need, the NOISE study team developed the Lifetime Exposure to Noise and Solvents Questionnaire (LENS-Q; Griest et al, 2021), the first questionnaire to capture military occupational, non-military occupational, and non-occupational noise and ototoxicant exposure over the course of an individual’s life.

The LENS-Q captures the exposure frequency and duration of each exposure, as well as the use of protective equipment. These data are combined with estimated sound levels to calculate a noise-exposure score. Individuals with higher noise-exposure scores had greater odds of tinnitus and hearing loss than individuals with the lowest noise exposure, indicating that the LENS-Q has good construct validity (Griest et al, 2021). With input from DoD subject-matter experts, the LENS-Q was recently revised to better capture military-noise exposures.

Understanding Auditory Outcomes

Early data from the NOISE study have begun to fill critical knowledge gaps regarding tinnitus and hearing loss in military service members and Veterans. Previous studies addressing these gaps typically relied upon the extraction of diagnostic codes from health-care records or upon data from non-generalizable clinical samples. These datasets do not capture undiagnosed cases of hearing loss and tinnitus, which are important to determine and interpret the true incidence and prevalence of these conditions.

These methodological limitations are exacerbated by the propensity of hearing science to apply definitions of hearing loss that may not be sensitive to early noise-induced changes and to report hearing loss as averages across frequencies. The NOISE study is uniquely designed to overcome these limitations, with broad inclusion criteria and the direct collection of audiometric data and military service history.

Despite the fact that all service members are exposed to noise during their military careers (Yankaskas, 2013), little is known about the prevalence of hearing loss among post-9/11 Veterans based on audiometric criteria (Theodoroff et al, 2015).

A cross-sectional analysis of NOISE study data from 403 Veterans and 287 service members revealed low-frequency (0.25–2 kHz) hearing loss in 13 percent of Veterans and 8 percent of service members (n=287), high-frequency (3–8 kHz) hearing loss in 25 percent of Veterans and 17 percent of service members, and extended-high-frequency (9−16 kHz) hearing loss in 42 percent of Veterans and 39 percent of service members (Henry et al, 2020a).

Tinnitus was present in 53 percent of the entire sample. Hearing loss and tinnitus were more prevalent in participants who were older, had more years of military service, and had higher military exposure to noise, blasts, and TBI (Henry et al, 2020a).

NOISE study data have also been used to estimate the average change in service members’ hearing and to evaluate the effects of noise on changes in hearing over time. This was accomplished by linking DoD audiometric surveillance data, collected as part of a hearing-conservation program, to data describing demographic and military service characteristics obtained from individuals enrolled in the NOISE study (Reavis et al, 2021).

Military surveillance audiograms from young service members (median age=20) during an initial military service period (median service duration=six years) were analyzed for hearing-threshold changes. The greatest rates of change were noted in the higher frequencies, consistent with noise-exposure patterns observed historically in the audiogram. Additionally, data gathered to date suggest that hearing-threshold levels in some military personnel in high noise exposure occupations appear to decline at a faster rate than would be expected for their age group.

Beyond noise, other risk factors associated with modern military service may impact and interact with hearing health, including exposure to ototoxic chemicals, blast injury, TBI, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These complex potential relationships are being explored using the extensive data collected by the NOISE study.

One such analysis (Theodoroff et al, 2019) addressed the relationship between blast exposure and decreased sound tolerance (DST). People with DST perceive everyday sounds (e.g., going to the grocery store) as uncomfortable or overwhelming, even when sound levels are low to moderate. In the NOISE study, DST was prevalent in both service members (29 percent) and Veterans (40 percent). Among Veterans, the prevalence of DST was 1.9 times higher among those with a history of blast exposure than for those without that history.

Another analysis examined the association between blast exposure and self-reported hearing difficulty among service members and Veterans with normal hearing and explored the potential mediating role of PTSD (Reavis et al, submitted for publication). The NOISE study team found that 13 percent of participants without PTSD had a self-reported hearing difficulty and 49 percent of those with probable PTSD had a self-reported hearing difficulty. A high proportion (41 percent) of the observed association between blast exposure and self-reported hearing difficulty was likely mediated by a positive screen for PTSD.

Finally, the NOISE study continues to explore the potential impacts of tinnitus on military service members. The study’s findings indicate that tinnitus adversely affects service members’ job performance, concentration, anxiety, depression, and sleep (Henry et al, 2019). These findings highlight the need for continued funding and research into tinnitus prevalence, outcomes, and prevention.

Critical Milestones Ahead

Answering the most important research questions addressed by the NOISE study, including the question of delayed-onset hearing loss and/or tinnitus, will require ongoing data collection from the enrolled study cohort over many years. The collection of five-year follow-up audiometric data began in 2019 and the team looks forward to collecting the first 10-year follow-up data in 2024.

To achieve the lifetime follow-up recommended by the IOM (Humes et al, 2006), we hope to continue data collection at both sites until 2034 or beyond. New participants are being enrolled on a continuing basis to increase the statistical power of the cohort and to compensate for attrition.

The NOISE study continues to meet and overcome the challenges of collecting longitudinal hearing-health and tinnitus data while releasing key findings along the way. Insights from hearing-health and tinnitus research are crucial to optimize military job performance and safety, improve Veteran health outcomes and well-being, and reduce the institutional cost burden of health care and compensation related to tinnitus and hearing loss.

Long-term research findings from the NOISE study will be critical to fill pressing knowledge gaps about how military risk factors affect hearing-health outcomes and will ultimately contribute to improved outcomes for those who dedicate themselves to military service.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program Investigator-Initiated Research Award (PR121146), the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Joint Warfighter Medical Research Program under Awards No. W81XWH-17-1-0020 and JW160036, and a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Research Career Scientist Award (1 IK6RX002990-01).

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA RR&D National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (VA RR&D NCRAR Center Award, C9230C) at the VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon, as well as the Department of Defense Hearing Center of Excellence in San Antonio, Texas.

The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and may not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

REDCap is supported by an Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute grant (UL1TR002369).

References

Brungart D, Walden B, Cord M, et al. (2017) Development and validation of the speech reception in noise test (SPRINT). Hear Res 349:90–97.

Cunningham L, Tucci L. (2017) Hearing loss in adults. N Engl J Med 377(25):2465–2473.

Davis A, Hoffman H. (2019) Hearing loss: rising prevalence and impact. Bull WHO 97(10):646–646A.

Griest S, Bramhall N, Reavis K, Theodoroff S, Henry J. (2021) Development and initial validation of the lifetime exposure to noise and solvents questionnaire (LENS-Q) in U.S. service members and veterans. Am J Audiol published ahead of print May 17, 2021, at https://pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/2021_AJA-20-00145 (accessed May 17, 2021).

Harris P, Taylor R, Minor B, et al. (2019) The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform (95):103208.

Henry J, Griest S, Austin D, et al. (2016) Tinnitus screener: Results from the first 100 participants in an epidemiology study. Am J Audiol 25(2):153–160.

Henry J, Griest S, Blankenship C, et al. (2019) Impact of tinnitus on military service members. Mil Med 184(Supplement 1):604–614.

Henry J, Griest S, Reavis K, et al. (2020a) Noise outcomes in service members epidemiology (NOISE) study: design, methods, and baseline results. Ear Hear published ahead of print December 16, 2020, at https://journals.lww.com/ear-hearing/Abstract/9000/Noise_Outcomes_in_Servicemembers_Epidemiology.98575.aspx (accessed December 16, 2020).

Henry J, Reavis K, Griest S, et al. (2020b) Tinnitus: an epidemiologic perspective. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 53:481–499.

Humes L, Joellenbeck L, Durch J (Eds). (2006) Noise and Military Service: Implications for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus. The National Academies Press: Washington, D.C.

Reavis K, McMillan G, Carlson K, et al. (2021) Occupational noise exposure and longitudinal hearing changes in post-9/11 U.S. military personnel during an initial period of military service. Ear Hear published ahead of print February 4, 2021, at https://journals.lww.com/ear-hearing/Abstract/9000/Occupational_Noise_Exposure_and_Longitudinal.98556.aspx (accessed February 4, 2021).

Reavis K, Snowden J, Henry J, Lewis M, Gallun F, Carlson K. (submitted for publication) Blast exposure and self-reported hearing difficulty in a normal-hearing military population: The mediating role of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Theodoroff S, Reavis K, Griest S, Carlson K, Hammill T, Henry J. (2019) Decreased sound tolerance associated with blast exposure. Sci Rep 9(1):10204.

Theodoroff SM, Lewis MS, Folmer RL, Henry JA, Carlson KF. (2015) Hearing impairment and tinnitus: prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes in U.S. service members and veterans deployed to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Epidemiol Rev 37:71-85.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021) Veterans Benefits Administration annual reports, 2007–2018. www.benefits.va.gov/REPORTS/abr/ (accessed April 16, 2021).

Yankaskas, K. (2013) Prelude: Noise-induced tinnitus and hearing loss in the military. Hear Res 295:3–8.