By Alissa Hoyme and M. Dawn Nelson

This article is a part of the May/June 2018, Volume 30, Number 3, Audiology Today issue.

The mandatory cessation of medications before vestibular testing is debatable. Patients seen for vestibular testing commonly are given pre-instructions that include a request to discontinue medications during the pre-evaluation time; typically for two days. It is unclear if these medication restrictions are based on scientific evidence or on tradition. Here we provide evidence for discontinuing or continuing medications and other substances before vestibular testing. We also will discuss how to determine an appropriate timeline for discontinuation of various drugs before vestibular testing. It is imperative that the clinician be aware of the effects of patient medications on vestibular test results for accurate test interpretation.

Currently no universal guidelines exist that specify for how long or from which medications a patient should refrain before vestibular testing. Individual practices must develop their own rules. Drugs that generally are considered to affect vestibular test results include antihistamines, antiemetics, sleeping pills, barbiturates, caffeine, amphetamines, alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco (Hain, 2014). Other clinics do not ask patients to discontinue medications, and clinicians document the medications that the patient is taking and interpret the results accordingly (Beck, 2013).

Designing Pre-Instructions for Vestibular Testing

There are several things to consider when designing pre-instructions for vestibular testing. Drugs that affect vestibular function should be discontinued whenever possible, but there are several categories of drugs that should not be discontinued, namely life-sustaining medications or those with no documented effects on test results. If a life-sustaining medication could affect test results it should be documented in the report. In addition, two issues that have not received enough attention when designing vestibular testing instructions are the potential for withdrawal when abruptly discontinuing medications and the amount of time that the effects of medications persist after a patient stops taking them.

Drugs that Affect the Vestibular System

Vestibular Suppressants

These drugs work by suppressing neuronal activity within the vestibular systems of both sides, which has the clinical effect of reducing the asymmetry between ears (Chabbert, 2016). This vestibular suppression can cause a bilateral weakness during caloric testing.

Antihistamines can suppress the vestibular system and reduce dizziness. Some examples include meclizine (Antivert®), diphenhydramine (Benadryl®), and dimenhydrinate (Dramamine®; Rascol et al, 1995). Scopolamine, an anticholinergic typically used in the form of a transdermal patch, also is used to treat dizziness and motion sickness (Chabbert, 2016). Benzodiazepines reduce anxiety and mimic the action of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA in the central or peripheral vestibular system (Chabbert, 2016). Examples of benzodiazepines include diazepam, lorazepam, and clonazepam (Chabbert, 2016). Receptors for several neurotransmitters are found in the peripheral and central vestibular system, and drugs that act on these receptors also have the potential to affect vestibular system function (Soto and Vega, 2010).

Alcohol

Alcohol intoxication can affect the results of several vestibular tests (Goebel et al, 1995). However, positional alcohol nystagmus (PAN) is probably encountered more often in a vestibular clinic. PAN I begins about 30 minutes after drinking begins and lasts for several hours, with nystagmus beating toward the lower ear. After a period of no nystagmus, PAN II begins about five to 10 hours after drinking stops, with nystagmus beating toward the upper ear (Fetter et al, 1999). PAN might even occur beyond 24 hours (Hill et al, 1973). A restriction on alcohol for 48 hours before testing is reasonable given the duration of this effect.

Marijuana

Spector (1974) found an increase in positional nystagmus and a decrease in slow phase velocity during caloric testing in heavy marijuana users. A more recent case describes a patient who presented with vertigo and nystagmus, which were attributed to marijuana use (Kibby and Halcomb, 2013). Dizziness and vertigo have been reported as side effects of medical cannabinoid drugs, and cannabinoid CB1 receptors have been found in the vestibular nuclear complex (Smith et al, 2006).

Tobacco

Tobacco has the potential to affect test results but only for a very short period of time. Smoking tobacco can cause upbeating nystagmus in the primary position that can be observed with vision denied (Sibony et al, 1987). This effect lasts for about 10 to 20 minutes following smoking. Tobacco smoking also can cause abnormalities in smooth pursuit, lasting about five minutes after smoking (Sibony et al, 1988).

Drugs that Do Not Affect the Vestibular System

Patients often are asked to discontinue drugs for vestibular testing that might not affect the results at all. More research is always needed, but current evidence indicates that patients can continue to take some antinausea medications and allergy medications and consume caffeine before testing. If results are not affected, patient comfort should be prioritized. Shortening the list of drugs to discontinue can also result in fewer canceled or rescheduled appointments.

Ondansetron

Medications for nausea belong to several different drug classes. Many drugs that treat nausea affect the vestibular system via anticholinergic and antihistaminic actions (Chabbert, 2016). Setrons, however, are different and work on serotonin receptors. A common example is ondansetron, which has the brand name Zofran® (Chabbert, 2016). Ondansetron likely has no effect on vestibular test results (Hain, 2014). Patients in the early stage of vestibular neuritis who received ondansetron were found to have better vestibular function than those who received metoclopramide, indicating a possible protective effect (Venail et al, 2012). If that is the case, patients should be allowed to keep taking ondansetron during testing.

Second-Generation Antihistamines

Second-generation antihistamines are used as “nondrowsy” allergy medications. Examples include loratadine (Claritin®) and fexofenadine (Allegra®). More research is needed, but patients may be able to continue these medications with no effect on vestibular test results. Second-generation antihistamines have less effect on the central nervous system than first-generation antihistamines (Cheung et al, 2003).

Caffeine

Patients often are asked to discontinue caffeine before testing, but current evidence indicates that this is not necessary. Felipe et al (2005) found that caffeine has no effect on caloric results and that caffeine withdrawal can contribute to an increase in anxiety, headache, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting during testing. The authors argued that allowing patients to continue to consume caffeine contributes to a relaxed but alert state that is ideal for testing (Felipe et al, 2005). Similarly, McNerney et al (2014) found that moderate caffeine consumption does not have a statistically or clinically significant effect on calorics or cVEMPs.

| DRUG | BRAND NAME | CLASS | HALF-LIFE | DURATION OF ACTION |

| BENZODIAZEPINES | ||||

| Alprazolam | Xanax® | Benzodiazepine | 12–15 hours (immediate release), 11–16 ER | |

| Clonazepam | Klonopin® | Benzodiazepine | 17–60 hours | 6–12 hours |

| Diazepam | Valium® | Benzodiazepine | 1–12 days | 20–80 hours |

| Lorazepam | Ativan® | Benzodiazepine | 10–20 hours | 12–24 hours |

| ANTIHISTAMINES | ||||

| Meclizine | Antivert® | Antihistamine | 6 hours | |

| Diphenhydramine | Benadryl® | Antihistamine | 2.5–9.5 hours | 6–8 hours |

| Hydroxyzine | Atarax® | Antihistamine | 3 hours | 4–6 hours |

| Fexofenadine | Allegra® | Antihistamine (2nd gen) |

14.4 hours | |

| Loratadine | Claritin® | Antihistamine (2nd gen) |

8.4 hours (28 for active metabolites) | |

| Cetirizine | Zyrtec® | Antihistamine (2nd gen) |

8.3 hours | |

| OPIOIDS | ||||

| Hydrocodone | Hysingla ER® Zohydro ER® |

Opioid | 7–9 hours | |

| Oxycodone | OxyContin® | Opioid | 2–3 hours | 3–6 hours |

| Codeine | Opioid | 2.5 hours | 4–6 hours | |

| Acetaminophen/oxycodone | Percocet® | Opioid | See individual drugs | |

| Hydromorphone | Dilaudid® | Opioid | 2.5–4 hours | 4–5 hours |

| Acetaminophen/hydrocodone | Vicodin® | Opioid | See individual drugs | |

| ANTIEMETICS | ||||

| Prochlorperazine | Compro® | Antiemetic | Unknown | 3–12 hours |

| Promethazine | Phenergan® | Antihistamine | Unknown | <12 hours |

| Scopolamine | Anticholinergic | 4.5 hours, 9.5 hours for transdermal | ||

| Ondansetron | Zofran® | Setron | 4 hours | |

| Dimenhydrinate (diphenhydramine/8-chlorotheophylline) | Dramamine® | Antihistamine/stimulant (antiemetic) | 1–4 hours | |

| Metoclopramide | Reglan® | Antiemetic | 4–6 hours | 1–2 hours |

| ANTIDEPRESSANTS | ||||

| Citalopram | Celexa® | SSRI | 35 hours | 1–2 days |

| Fluoxetine | Prozac® | SSRI | 2–6 days | |

| Paroxetine | Paxil® | SSRI | 21 hours | |

| Sertraline | Zoloft® | SSRI | 26 hours | |

| Duloxetine | Cymbalta® | SSNRI | 12 hours | |

| Nortriptyline | Pamelor® | Tricyclic antidepressant | 18–24 hours | |

| Venlafaxine | Effexor XR® | SSNRI | 3–7 hours | |

| BARBETURATES | ||||

| Phenobarbital | Luminal® | Barbiturate | 53–118 hours | |

| Pentobarbital | Nembutal® | Barbiturate | 5–50 hours | |

| DIURETICS | ||||

| Furosemide | Lasix® | Loop diuretic | 2 hours | 6–8 hours |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Microzide® | Thiazide diuretic | 6–15 hours | 6–12 hours |

| Triamterene | Potassium-sparing diuretic | 1.5–2.5 hours | 6–12 hours | |

| HYPNOTICS | ||||

| Eszopiclone | Lunesta® | Hypnotic | 6 hours | |

| Zolpidem | Ambien® | Hypnotic | 1.5–8.5 hours | |

| Ramelteon | Rozerem® | Melatonin receptor agonist | 1–2.5 hours; 2–5 hours for metabolite | |

| ANTICONVULSANTS | ||||

| Carbamazepine | Tegretol® | Anticonvulsant | 25–65 hours (8–29 hours with long-term use) | |

| Gabapentin | Neurontin® | Anticonvulsant | 5–7 hours | |

| Levetiracetam | Keppra® | Anticonvulsant | 6–8 hours | 12 hours |

| Topiramate | Topamax® | Anticonvulsant | 21 hours | |

| Valproate sodium | Depacon® | Anticonvulsant | 6–16 hours | |

| OTHER | ||||

| Naproxen | Naprosyn® | NSAID | 10–21 hours | 7 hours |

| Ibuprofen | Advil® | NSAID | 2–4 hours | 4–6 hours |

| Aspirin | Salicylate (NSAID) | 15 minutes to 6 hours |

1–4 hours | |

| Acetaminophen | Tylenol® | Para-aminophenol derivative | 2–3 hours | 3–4 hours |

| Alcohol | CNS depressant | Varies | ||

| Caffeine | CNS stimulant | 3–7 hours | ||

| Nicotine | CNS stimulant | 1–3 hours (15–20 hours for metabolite) | ||

| THC/dronabinol | Marinol® | Cannabinoid | Alpha phase: 4 hours, Beta phase: 25–36 hours | |

TABLE 1. Shows drugs and their half-lives to illustrate the differences in how long various drugs stay in the body. Duration of action is also given when available. The drugs selected are many that might be of interest in a vestibular clinic.

Withdrawal and Discontinuation Effects

Some drugs can cause withdrawal symptoms when stopped abruptly. The effects can range from mildly unpleasant to life-threatening. Common classes of drugs associated with significant withdrawal include SSRIs (a type of antidepressant), some antihypertensives, corticosteroids, statins, opioids, benzodiazepines, and alcohol (Papadopoulos and Cook, 2006). For many of these drugs withdrawal symptoms begin within one or two days, which is the period of time they are often discontinued before testing.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal can cause seizures, status epilepticus, coma, and death (Hu, 2011). Even in less severe cases, benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can include nausea, dizziness, and headaches (Hu, 2011). These symptoms can affect vestibular testing.

Discontinuation effects have long been reported for tricyclic antidepressants, and these effects increasingly are becoming recognized for SSRIs as well (Haddad, 1998). Dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, headache, and lethargy are the most common symptoms of SSRI discontinuation syndrome, with ataxia, vertigo, sensations of being pulled to one side, and “electric shock” sensations with head movements also being reported (Haddad, 1998).

Another category of medications commonly known to cause withdrawal symptoms are opioid pain medications, which patients may be asked to discontinue due to their sedating effects. Symptoms of withdrawal include anxiety, increased blood pressure, and nausea (Howland, 2010). While unpleasant, these symptoms are usually not dangerous. Withdrawal occurs primarily with chronic use (Howland, 2010). As with SSRIs, more research is needed to weigh the potential for vestibular effects with the potential for patient discomfort from stopping these medications.

Alcohol withdrawal is usually mild, but in severe cases can lead to delirium tremens and withdrawal seizures, and these more severe forms of withdrawal can be fatal (McKeon et al, 2008). Alcohol should be discontinued before vestibular testing, but alcohol-dependent individuals should be tested after detoxification is complete, which might require medical supervision.

Patients typically are asked to continue taking medications for seizures, but anticonvulsants can be used for other purposes as well, such as pain, migraine, and bipolar disorder (Norton, 2001). Carbamazepine and gabapentin are both common anticonvulsants and have both been shown to affect saccades and postural control (Noachtar et al, 1998). There is the potential for withdrawal symptoms with anticonvulsants, and gabapentin withdrawal can resemble alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal (Norton, 2001). Due to the potential for withdrawal effects, clinicians should note in their report if a patient is taking one of these drugs and the results should be interpreted accordingly.

In most cases, patients should continue to take medications that have significant negative withdrawal effects. If these medications have the potential to affect test results, the fact that a patient is taking them should be noted in the report. If these drugs must be discontinued, they should be tapered under the supervision of the patient’s physician.

| CATEGORY | DISCONTINUE? | EXAMPLES |

| Known vestibular effects | Yes (if possible) | Alcohol, Antidepressants, Antiemetics, Benzodiazepines, First-generation antihistamines, Marijuana, Opioids, Sedatives, and Tobacco (up to 20 minutes) |

| Significant withdrawal effects | No (or with caution) | Alcohol (if dependent), Anticonvulsants, Antidepressants, Benzodiazepines, Blood pressure medications, Corticosteroids, Opioids, Statins |

| No vestibular effects | No | Caffeine, Setrons (e.g., Zofran), Possibly second generation antihistamines (e.g., fexofenadine) |

| Life-sustaining | No | Medications for heart conditions, diabetes, blood pressure, epilepsy, and other chronic health conditions |

TABLE 2. Shows drug categories for vestibular testing with some examples and a simplified answer as to whether they should be discontinued.

Drug Half-Life and Duration of Action

The amount of time that different drugs stay in the body varies widely. Stopping a drug 48 hours before testing can be excessive for some drugs and not nearly long enough for others. The half-life of a drug is defined as “the time necessary for the amount of drug present in the body, or its concentration in serum or plasma, to fall by 50 percent” (Greenblatt, 1985). While half-life itself has limited utility, it is one of the most common pharmacokinetic properties listed in drug references.

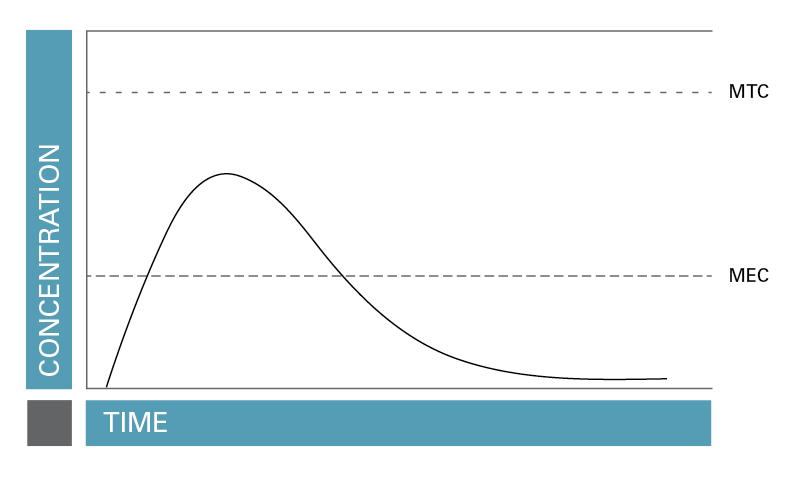

The duration of action, that is, the length of time that the level of a drug is high enough to be effective but not so high that it is toxic (Rosenbaum, 2017) may be a better way to represent the length of the effect of a drug. FIGURE 1 illustrates the concept of duration of action.

TABLE 1 shows drugs and their half-lives to illustrate the differences in how long various drugs stay in the body. Duration of action is also given when available. The drugs selected are many that might be of interest in a vestibular clinic.

FIGURE 1. Duration of action, that is, the length of time that the level of a drug is high enough to be effective but not so high that it is toxic.

Evidence-Based Pre-Instructions for Vestibular Testing

Medications can be grouped into four categories when designing vestibular test instructions: (1) medications with known vestibular effects, (2) life-sustaining medications, (3) medications with serious withdrawal effects, and (4) medications with no vestibular effects. Some drugs can fall into more than one category. Table 2 shows drug categories for vestibular testing with some examples and a simplified answer as to whether they should be discontinued.

Conclusion

The impact of discontinuing medications before vestibular testing needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis. It is important that audiologists have an understanding of pharmacology. At the very least, information of drug and withdrawal effects should be included in vestibular courses, and possibly an entire course in pharmacology should be offered. By asking patients to discontinue medications, we are making recommendations that have implications that affect patient safety. Patients should be encouraged to discuss any concerns about discontinuing medications with their primary care physician or pharmacist. It is also important to understand the effects of medications that patients are allowed to continue taking during testing so that the results can be accurately interpreted.

References for Table 1

National Center for Biotechnology Information (2017)

Nursing Drug Handbook (2018)

References

Beck DL. (2013) VEMPs, rotational tests, and platform posturography. Interview with Devin L. McCaslin, PhD. American Academy of Audiology. www.audiology.org/news/vemps-rotational-tests-and-platform-posturography-interview-devin-l-mccaslin-phd (accessed January 29, 2017).

Chabbert C. (2016) Principles of vestibular pharmacotherapy. Handb Clin Neurol 137 (3rd series) Neuro-Otology:207–218 .

Cheung BS, Heskin R, Hofer KD. (2003) Failure of cetirizine and fexofenadine to prevent motion sickness. Ann Pharmacother 37:173–177.

Felipe L, Simoes LC, Goncalves, DU, Mancini PC. (2005) Evaluation of the caffeine effect in the vestibular test. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol 71(6):758–762.

Fetter M, Haslwanter T, Bork M, Dichgans J. (1999) New insights into positional alcohol nystagmus using three-dimensional eye-movement analysis. Ann Neurol 45:216–223.

Goebel JA, Dunham DN, Rohrbaugh JW, Fischel D, Stewart PA. (1995) Dose-related effects of alcohol on dynamic posturography and oculomotor measures. Acta Oto-Laryngol Supp, 520:212–215.

Greenblatt DJ. (1985) Elimination half-life of drugs: value and limitation. Ann Rev Med 36:421–427.

Haddad P. (1998) The SSRI discontinuation syndrome. J Psychopharmacol 12(3):305–313.

Hain TC. (2014) Drug effects and vestibular testing. Dizziness-and-balance.com. www.dizziness-and-balance.com/testing/ENG/drugs.html (accessed 11/17/2016).

Hill RJ, Collins WE, Schroeder DJ. (1973) Influence of alcohol on positional nystagmus over 32-hour periods. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 82:103–110.

Howland RH. (ed.) (2010) Potential adverse effects of discontinuing psychotropic drugs. Part 4: Benzodiazepine, glutamate, opioid, and stimulant drugs. J Psychosoc Nurs 48(9):11–14.

Hu X. (2011) Benzodiazepine withdrawal seizures and management. J Okla State Med Assoc 104(2):62–65.

Kibby T, Halcomb SE. (2013) Toxicology observation: Nystagmus after marijuana use. J Foren Leg Med 20:345–346.

McKeon A, Frye MA, Delanty N. (2008) The alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 79:854–862.

McNerney K, Coad ML, Burkard R. (2014) The influence of caffeine on calorics and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (cVEMPs). J Am Acad Audiol 25:261–267.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. The PubChem Project. pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed October 2017).

Noachtar S, von Maydell B, Fuhry L, Büttner U. (1998) Gabapentin and carbamazepine affect eye movements and postural control differently: A placebo-controlled investigation of CNS side effects in healthy volunteers. Epilepsy Res 31:47–57.

Norton JW. (2001) Gabapentin withdrawal syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol 24(4):245–246.

Nursing2018 Drug Handbook (2018) Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Papadopoulos S, Cook AM. (2006) You can withdraw from that? The effects of abrupt discontinuation of medications. Orthopedics 29(5):413–417.

Rascol O, Hain TC, Brefel C, Benazet M, Clanet M, Montastruc JL. (1995) Antivertigo medications and drug-induced vertigo: A pharmacological review. Drugs 50(5):777–791.

Rosenbaum SE. (2017) Introduction to pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. In: SE Rosenbaum (Ed.), Basic Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1–18.

Sibony PA, Evinger C, Manning KA. (1987) Tobacco-induced primary-position upbeat nystagmus. Ann Neurol 21(1):3–58.

Sibony PA, Evinger C, Manning KA. (1988) The effects of tobacco smoking on smooth pursuit eye movements. Ann Neurol 23(3):238–241.

Smith PF, Ashton JC, Darlington CL. (2006) The endocannabinoid system: A new player in the neurochemical control of vestibular function? Audiol Neurotol 11:207–212.

Soto E, Vega R. (2010) Neuropharmacology of vestibular system disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol 8:26–40.

Spector M. (1974) Chronic vestibular and auditory effects of marijuana. Laryngoscope 84(5): 816–820.

Venail F, Biboulet R, Mondain M, Uziel A. (2012) A protective effect of 5-HT3 antagonist against vestibular deficit? Metoclopromide versus ondansetron at the early stage of vestibular neuritis: A pilot study. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 129:65–68.