By James W. Woods and Sarah M. Theodoroff

This article is a part of the November/December 2019, Volume 31, Number 6, Audiology Today issue.

Tinnitus management is nuanced and many approaches can be taken, some supported by more evidence than others. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) repeatedly has been shown to be an effective approach to help patients manage their tinnitus distress. This article provides a general overview of what CBT entails and when to consider referring your tinnitus patients to a health-care provider who specializes in CBT.

To date, there is no cure for tinnitus. However, no cure is not equivalent to no treatment. This distinction offers a place to start a conversation with patients about what can be done to address their tinnitus complaints.

It is of paramount importance to avoid using the phrase “nothing can be done” when speaking with patients. This type of statement can be detrimental to their ability to cope with their condition.

Although there is no consensus regarding the best approach to use for tinnitus management, there are clinical practice guidelines that provide a thorough review of current approaches, as well as evidence supporting or opposing these approaches (Tunkel et al, 2014). Manning (2019) provides an excellent summary of the top 10 essential components of tinnitus assessment and management for clinicians in the May/June 2019 issue of Audiology Today.

Both Tunkel and Manning address management options that are within the scope of practice of audiology and recommend an interdisciplinary approach when there are emotional and psychological considerations falling outside of the audiologist’s scope of practice. One such approach is CBT, a form of psychotherapy that can be administered for a variety of conditions.

CBT for tinnitus has been endorsed by the American Academy of Audiology, American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, and American Speech-Language-Hearing Association as an effective treatment approach for tinnitus supported by strong evidence.

Even so, many audiologists are not familiar with CBT or how it could be applied to help tinnitus patients. Additionally, many audiologists are uncertain which tinnitus complaints might warrant a referral for CBT and how to explain to a patient that CBT could help them manage their tinnitus. This article will help clarify these uncertainties.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT was developed in the 1960s by psychiatrist Dr. Aaron Beck as a form of psychotherapy for depression (Beck, 2011). Beck realized that distorted, or what he describes as inaccurate, thoughts and beliefs were prominent features of depression and these features could be targeted in cognitive therapy, which was later expanded to CBT.

Overall, CBT is based on a conceptual model that describes the interplay between thoughts (i.e., cognitions), behaviors, and emotions and provides practical strategies to employ when the relationships among these elements goes awry.

At its core, CBT is focused on problem-solving to help patients improve their overall sense of well-being. Mental health providers often implement CBT using a flexible paradigm incorporating methods from established psychological approaches.

CBT for tinnitus is intended to help patients cope with tinnitus and is not intended as a cure or an approach to make the tinnitus quieter. Cima et al (2014) provide an excellent summary of the history of CBT for tinnitus, starting in the 1980s and continuing through to the present day.

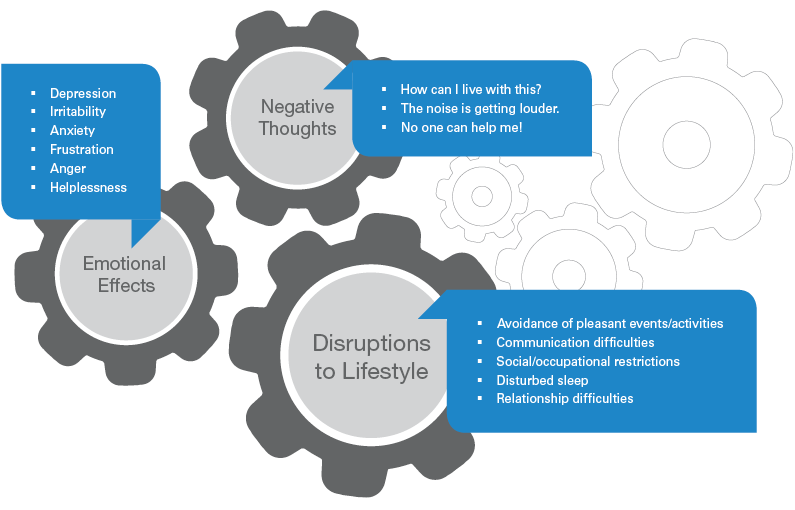

FIGURE 1. Interplay and examples of negative thoughts, emotions, and lifestyle disruptions associated with tinnitus distress. Adapted with permission from Newman and Sandridge (2016) Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, SIG 7.

Within the CBT framework, concepts such as dysfunctional thinking and behaviors are discussed. These terms refer to negative, distorted, or emotionally distressing thoughts leading to unhelpful behaviors (Beck, 2011).

As illustrated in FIGURE 1, a tinnitus patient’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are conceptualized as elements that can influence and perpetuate one another. These components do not necessarily interact in a cyclical fashion.

Negative thoughts, such as “no one can help me,” can lead to lifestyle disruptions (e.g., avoidant behaviors) and can contribute to negative emotional effects (e.g., depression, frustration, etc.) and vice versa.

Dysfunctional thoughts and feelings may contribute to, and reinforce, negative behavioral patterns in subtle and automatic ways. This makes it difficult for an individual to recognize the unhelpful alliance their thoughts and feelings have formed with their behaviors.

For example, patients who report they are most distressed by their tinnitus when trying to fall asleep may stay up watching television or start projects late at night to put off going to bed. They may not realize that these avoidant behaviors can contribute to poor sleep and, in turn, negatively affect their overall quality of life.

The underlying dysfunctional thought might be, “Trying to fall asleep is useless because my tinnitus is so loud it keeps me awake, and I’ll just toss and turn all night.”

CBT and Tinnitus

During CBT sessions, the patient and health-care provider work together to identify automatic dysfunctional thoughts that arise in scenarios like this. Next, the patient and provider work together to develop concrete plans for the patient to take control of his or her negative reactions and employ positive coping strategies with the goal of shifting attention away from the tinnitus.

CBT typically involves six to 10 weekly therapy sessions, either individually or in small groups. Each session addresses a specific topic, such as an educational overview of tinnitus, sleep hygiene, stress management, relaxation, and cognitive restructuring (Andersson, 2002).

The CBT process may look different for each patient. Therapy is tailored to meet the individual patient’s needs. What is similar across patients is the overall theme of using goal-oriented problem-solving techniques, assessing and responding to dysfunctional thoughts, and modifying negative behavior patterns.

Therapists may also incorporate aspects of other behavioral approaches, such as acceptance commitment therapy (ACT) and mindfulness, which are complementary practices to CBT.

ACT also addresses unhelpful thought processes. The primary difference between CBT and ACT is in the coping strategies employed.

With CBT, patients are encouraged to change their internal dialogue of negative thoughts through a technique called cognitive restructuring. With ACT, patients are encouraged to have an accepting attitude toward unwanted experiences such as pain, thoughts, feelings, and memories (Hayes et al, 1999).

Similarly, mindfulness is the meditative practice of being aware of sensations and allowing the present moment to unfold without judgment (Kabat-Zin, 1994).

Conceptually, these behavioral approaches have overlapping themes. Patients may be encouraged to use elements of multiple behavioral approaches to reduce their tinnitus distress.

CBT Resources

American Counseling Association

American Psychological Association

Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

|

When to Refer for Mental Health Services

There are many factors to consider as part of the clinical decision-making process to determine when an interprofessional approach is warranted.

If your patient has comorbid health conditions that are exacerbated by the tinnitus or expresses catastrophic thoughts when talking about his or her tinnitus (e.g., “I am suffering and will always suffer,” “I am desperate and terrified that I will no longer be able to function”), consider a referral to a psychologist or appropriate mental health provider.

It is within the audiologist’s scope of practice to address triggers (e.g., loud environments) as part of using a sound-based approach to tinnitus management. If the primary complaint is that tinnitus makes the patient feel anxious or depressed, consider referring your patient for outside services.

Multiple frameworks have been developed to aid the clinician in his or her decision-making process and may incorporate tenets of CBT. It is important to point out that employing ideas similar to those used in behavioral therapy is not the same thing as providing CBT for tinnitus.

In the VA system, progressive tinnitus management (PTM) is an evidence-based approach that focuses on teaching tinnitus patients a variety of coping skills. PTM has a hierarchical structure to evaluate and best meet a patient’s needs.

PTM is often multidisciplinary and can include up to five group educational sessions, some guided by an audiologist and others by a mental health provider. Overall, PTM describes a framework that promotes self-efficacy to manage reactions to tinnitus and includes a self-help workbook (Edmonds et al, 2017).

Another model to consider can be found at the Cleveland Clinic Tinnitus Management Clinic (TMC) (Newman and Sandridge, 2016). Both PTM and TMC take a stepped-care approach and use validated questionnaires to aid in the clinical decision-making process, resulting in patients receiving only the services that are needed.

The TMC framework outlines an interprofessional approach that includes audiology, dentistry, neurology, physical therapy (when somatosensory tinnitus is suspected to evaluate underlying head, neck, and/or jaw issues that might be treatable with manualized therapy), and psychology (for patients to receive CBT for tinnitus).

Helping Patients Manage Tinnitus

Because there is no effective treatment capable of reducing the perception of tinnitus, the focus should be on helping patients manage their reactions to tinnitus and not on reducing the perceived loudness or changing any other aspect of what the tinnitus sounds like. It is important that patients understand this distinction so they can develop clear and realistic treatment goals.

Often, there is a disconnect between clinicians and patients regarding treatment expectations (Husain et al, 2018). It is critical to find out what situation is most bothersome to the patient and have an honest conversation about realistic goals and expectations. That is the key to successful outcomes.

In general, if a clinician is unsure about what is or is not within their scope of practice to offer tinnitus patients, he or she should reach out to the appropriate professional organization for guidance.

Whenever tinnitus is exacerbated by triggers, anything that can help minimize the triggers often can help reduce the tinnitus distress as well. If patients report that their tinnitus gets worse when they experience stress, seeing a therapist who can help them manage their stress has the added benefit of resolving some of the tinnitus-related distress associated with that trigger.

Because stress management and CBT are outside an audiologist’s scope of practice in the United States, it is best to refer to appropriate providers for these services. Professionals trained to administer CBT include psychologists, counselors, and social workers.

If a clinician is unsure how to broach the subject of recommending that a tinnitus patient consider seeing a mental health provider, a conversation could be initiated as follows:

You’ve made progress, but reviewing your responses on this questionnaire* suggests you’ve plateaued using the approaches we’ve tried so far. I appreciate you sharing with me that your most bothersome situation is ___ (trouble sleeping/feeling anxious/etc.).

Our thoughts and beliefs affect our actions. Let me tell you a little bit about cognitive behavioral therapy, which has a lot of evidence behind it as an effective approach to manage tinnitus distress.

At its core, CBT focuses on problem-solving and developing coping skills for the situations in which you find your tinnitus to be bothersome. I think seeing a therapist who specializes in CBT would benefit you.

CBT is not a cure. It will not make your tinnitus go away, but it can help you find ways to pay less attention to it.

Note: There are multiple validated outcome instruments to choose from. The Tinnitus Functional Index is always a good choice because it was developed with treatment responsiveness central to its design (Meikle et al, 2012).

Considerations in Finding a Therapist

Many CBT for tinnitus protocols have been modeled after CBT for chronic pain. Therefore, health-care providers who have experience treating chronic pain (and insomnia) may find they already employ techniques similar to those recommended for tinnitus management (Kleinstäuber et al, 2013).

If there are no providers in your area who specialize in CBT for tinnitus, look for therapists who specialize in CBT for treating chronic pain and consider working together to best meet the needs of your tinnitus patients. Ultimately, developing collaborative relationships with professionals from other disciplines can only benefit your tinnitus patients.

Once those relationships are established, it is helpful to consult with your new colleagues and include screening instruments they recommend as part of the tinnitus assessment. This will aid in your clinical decision-making process and determine when referral to their services is appropriate.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by NIH NIDCD T35 Grant (#DC008764). This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (VA RR&D NCRAR Center Award; #C9230C) at the VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon. These contents do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.References

Andersson G. (2002) Psychological aspects of tinnitus and the application of cognitive–behavioral therapy. Clin Psych Rev 22(7):977–990.

Beck JS. (2011) Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond (Second Edition). New York: Guilford Press.

Cima RF, Andersson G, Schmidt CJ, Henry JA. (2014) Cognitive-behavioral treatments for tinnitus: A review of the literature. J Am Acad Audiol 25(1):29–61.

Edmonds CM, Ribbe C, Thielman EJ, Henry JA. (2017) Progressive tinnitus management level 3 skills education: A 5-year clinical retrospective. Am J Audiol 26(3):242–250.

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. (1999) Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford Press.

Husain FT, Gander PE, Jansen JN, Shen S. (2018) Expectations for tinnitus treatment and outcomes: A survey study of audiologists and patients. J Am Acad Audiol 29(4):313–336.

Kabat-Zinn J. (1994) Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. Hyperion.

Kleinstäuber M, Jasper K, Schweda I, Hiller W, Andersson G, Weise C. (2013) The role of fear-avoidance cognitions and behaviors in patients with chronic tinnitus. Cogn Behav Therapy 42(2):84–99.

Manning C. (2019) Tinnitus in 10: What every audiologist should know to provide research-based care. Audiol Today 31(3):16–26.

Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, et al (2012) The tinnitus functional index: Development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear 33(2):153–176.

Newman CW, Sandridge SA. (2016) Care path for patients with tinnitus: An interprofessional collaborative model. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups.

Tunkel DE, Bauer CA, Sun GH, et al (2014) Clinical practice guideline: Tinnitus. Otolaryng Head Neck 151(2_suppl).